What causes endometriosis? Scientists are closer to finding out

UC researcher featured on NPR podcast

The life and research of Katherine (Katie) Burns, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Public Health Sciences in the University of Cincinnati's College of Medicine and a prominent endometriosis researcher, was recently featured on Short Wave, NPR's science podcast. It came after she was the subject of an in-depth feature article in Science Magazine. She and the Science reporter, Meredith Wadman, were podcast guests.

REGINA BARBER: Katie wouldn't get an endometriosis diagnosis until she was 20. A diagnosis was validating, but it didn't provide relief. To manage the pain and exhaustion, she would take naps during the week and sleep through the weekend. She tried acupuncture, diet changes, even hypnosis. One outlet that helped distract Katie from the pain was studying, which led her to a research career. Eventually, she decided to study endometriosis. As she published her findings, Science reporter Meredith Wadman took notice.

MEREDITH WADMAN: I found Katie because this force of nature named Linda Griffith, who's at MIT and develops endometriosis organoids, put me onto Katie's work that was quite new and exciting and said, this is worth looking at.

BARBER: That new and exciting work revolved around the origins of endometriosis. Previous thinking pointed to hormones as the root cause of the disease, but Katie's work was pointing in a different direction. The first clue was that hormone treatments in people with endometriosis didn't always work.

BURNS: You can quiet disease, but you don't cure it. You don't get rid of it.

BARBER: Then an experiment in mice showed a completely unexpected result.

BURNS: I tried to convince myself that I did something wrong. The data wasn't making sense.

BARBER: Katie did the experiment over and over again and kept getting the same results.

BURNS: It really showed that the immune system seems to be that important starting piece and not the hormone receptors.

BARBER: Today on the show, Science journalist Meredith Wadman tells us how researchers are piecing together the surprising origins of a disease that affects millions of people worldwide and how it could lead to a simple, non-invasive test, better treatments, and perhaps, one day, a cure.

Listen to the full episode of the Short Wave podcast from NPR.

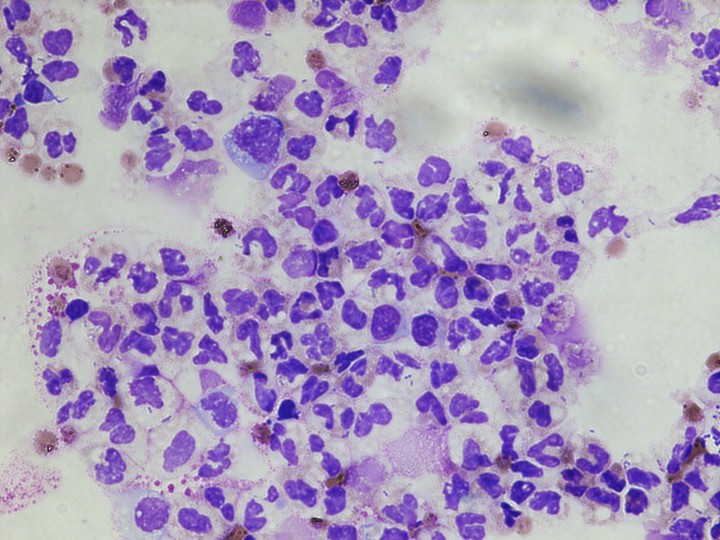

Featured image at top: Menstrual fluid shown under a microscope. Photo/Provided.

Related Stories

Sugar overload killing hearts

November 10, 2025

Two in five people will be told they have diabetes during their lifetime. And people who have diabetes are twice as likely to develop heart disease. One of the deadliest dangers? Diabetic cardiomyopathy. But groundbreaking University of Cincinnati research hopes to stop and even reverse the damage before it’s too late.

Is going nuclear the solution to Ohio’s energy costs?

November 10, 2025

The Ohio Capital Journal recently reported that as energy prices continue to climb, economists are weighing the benefits of going nuclear to curb costs. The publication dove into a Scioto Analysis survey of 18 economists to weigh the pros and cons of nuclear energy. One economist featured was Iryna Topolyan, PhD, professor of economics at the Carl H. Lindner College of Business.

App turns smartwatch into detector of structural heart disease

November 10, 2025

An app that uses an AI model to read a single-lead ECG from a smartwatch can detect structural heart disease, researchers reported at the 2025 Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association. Although the technology requires further validation, researchers said it could help improve the identification of patients with heart failure, valvular conditions and left ventricular hypertrophy before they become symptomatic, which could improve the prognosis for people with these conditions.