UC project targets pesky mosquitoes’ genes

Chemist finds female mosquitoes undergo more genetic changes

The next generation of mosquito control might target the pests’ reproductive genes.

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati examined genetic material of three species responsible for killing millions of people around the world each year. In a collaboration between UC’s chemistry and biology departments, researchers revealed the surprising genetic modifications female mosquitoes undergo, in part to create the next generation.

The study was published in the journal Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

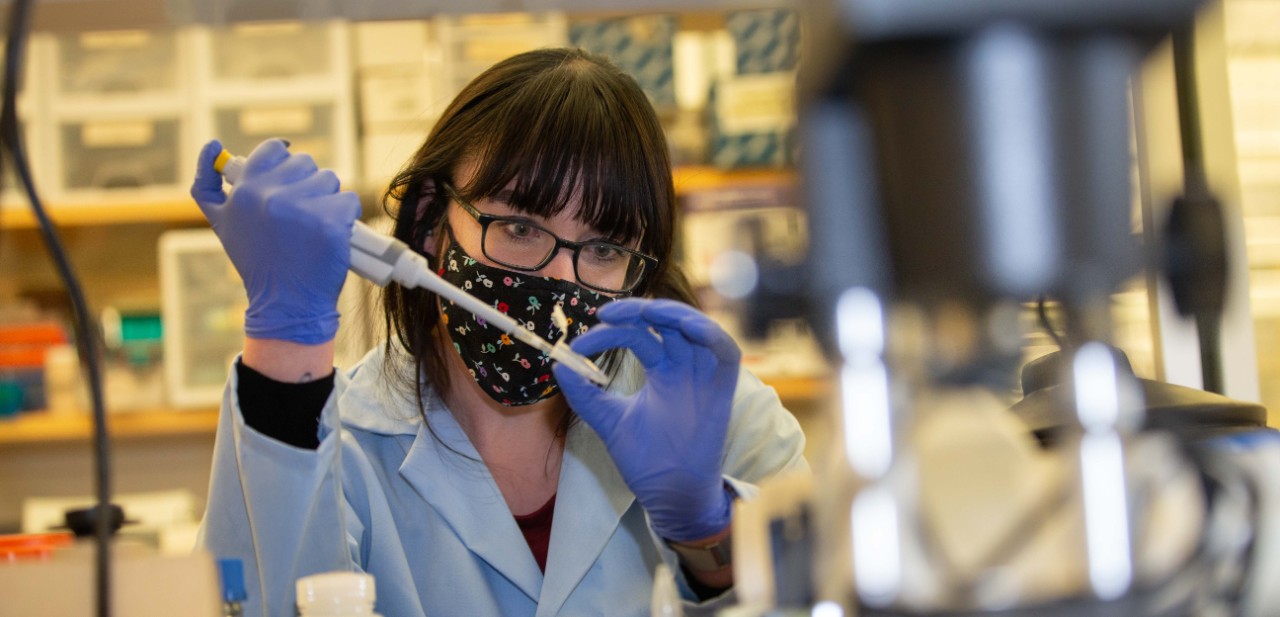

Students work with six species of mosquito in UC's biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Using tools called liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, researchers found as many as 33 genetic modifications in the transfer RNA of female mosquitoes. Like DNA, transfer RNA serves as the building blocks of life, communicating the genetic code from DNA to build new proteins that regulate the body’s tissues and organs.

“That’s important because it means there are different requirements for making proteins in males and females,” said Melissa Kelley, lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences.

“Proteins do a bunch of things — they do the housekeeping needed to keep an organism alive. And there are specialized ones that are created when females are getting ready to lay eggs,” Kelley said.

By better understanding these modifications at the molecular level, scientists might be able to find a new weapon to control mosquito populations.

UC graduate student Melissa Kelley works with six species of mosquito in UC's biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC is not alone. Researchers around the world are looking at ways to target the genes of mosquitoes to prevent mosquito-borne disease.

Mosquitoes might cause more human misery than virtually any other pest. More than 229 million people were diagnosed with malaria in 2019. Mosquitoes also carry yellow fever, dengue fever and West Nile virus, among others.

“There is a constant need for new methods of control,” Kelley said.

As carriers of multiple human diseases, understanding the mechanisms behind mosquito reproduction may have implications for remediation strategies.

Patrick Limbach, UC Office of Research

Mosquitoes were responsible for reshaping entire landscapes in the United States. Mosquito-control commissions funded with federal dollars launched massive projects to drain and fill wetlands in the 1930s. Pesticides soon replaced labor-intensive water management policies. The popular insect killer DDT was banned in 1972 after research discovered the toxin was accumulating in the food chain and affecting wildlife such as bald eagles.

Various tools are used to fight mosquitoes, from dispersing fish that feast on mosquito larvae to releasing hordes of sterile males into the wild. But pesticides remain a popular solution.

“And there have been reports of increased pesticide resistance in mosquitoes,” Kelley said.

UC student Melissa Uhran works in associate professor Joshua Benoit's biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC chemist Patrick Limbach, UC’s vice president for research, was a co-author of the paper.

“As carriers of multiple human diseases, understanding the mechanisms behind mosquito reproduction may have implications for remediation strategies,” Limbach said.

Students cultivate six species of mosquitoes in biologist and associate professor Joshua Benoit’s lab.

UC studied three of them for the genetic study: Aedes aegypti, Culex pipiens and Anopheles stephensi. The first, found in Africa, the Mediterranean and the southeastern United States, is a known infectious agent for yellow fever, dengue, Zika virus and chikungunya. Culex pipiens is a mosquito found around the world and has been linked to West Nile virus. The last is an Asian mosquito that has been linked to malaria outbreaks. All three species require a blood meal for reproduction.

Female and male mosquitoes have obvious physical differences. Typically smaller with fuzzy antennae, male mosquitoes don’t suck blood like females that need nutrients to make the next generation.

“We were curious if there were differences in how they make proteins,” Kelley said.

UC doctoral student Melissa Kelley, left, associate professor Joshua Benoit and undergraduate student Melissa Uhran pose in a biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC researchers found that female mosquitoes have a higher abundance of tRNA modifications than males. Female mosquitoes likely utilize chemical modifications to tRNA more abundantly than males, which could underlie factors associated with female reproduction.

UC undergraduate biology student Melissa Uhran said she was fortunate to take part in the study.

“It was a great opportunity. I’m grateful to get a chance to do it. It’s given me a lot of experience that will help me career-wise,” she said. “And I’ve learned a lot.”

UC’s project was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Featured image at top: UC student Melissa Kelley works in a biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Doctoral student Mellisa Kelley is studying chemistry in UC's College of Arts and Sciences. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Become a Bearcat

Do you like the idea of conducting your own biology research? Apply online or get more information about undergraduate enrollment by calling 513-556-1100. Learn more about UC's many undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

Sugar overload killing hearts

November 10, 2025

Two in five people will be told they have diabetes during their lifetime. And people who have diabetes are twice as likely to develop heart disease. One of the deadliest dangers? Diabetic cardiomyopathy. But groundbreaking University of Cincinnati research hopes to stop and even reverse the damage before it’s too late.

App turns smartwatch into detector of structural heart disease

November 10, 2025

An app that uses an AI model to read a single-lead ECG from a smartwatch can detect structural heart disease, researchers reported at the 2025 Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association. Although the technology requires further validation, researchers said it could help improve the identification of patients with heart failure, valvular conditions and left ventricular hypertrophy before they become symptomatic, which could improve the prognosis for people with these conditions.

Combination immunotherapy helps overcome melanoma treatment resistance

November 10, 2025

MSN highlighted research led by the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center's Trisha Wise-Draper showing a combination of immunotherapy medications can activate a robust immune response and help overcome treatment resistance in patients with refractory melanoma.